The port agent drove me through the container terminal, which looked just like the one in Osaka. After so many months and so much anticipation, just seeing the lurking ship on the quay was like a milestone.

The port agent drove me through the container terminal, which looked just like the one in Osaka. After so many months and so much anticipation, just seeing the lurking ship on the quay was like a milestone.

The port agent drove me through the container terminal, which looked just like the one in Osaka. After so many months and so much anticipation, just seeing the lurking ship on the quay was like a milestone.

The port agent drove me through the container terminal, which looked just like the one in Osaka. After so many months and so much anticipation, just seeing the lurking ship on the quay was like a milestone. |

| I think most people see such ships at a distance, where it's difficult to really feel their size. Being next to one, it looms up above you like a skyscraper. The smoothness and lack of windows in the hull makes it seem monolithic. |  |

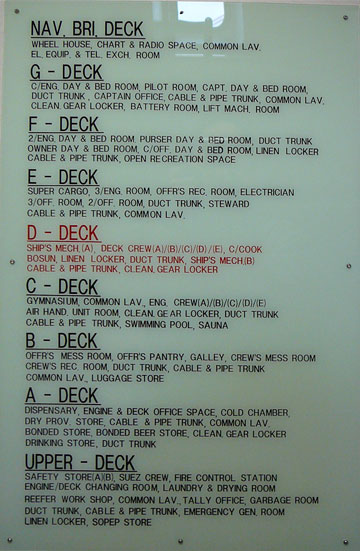

| Despite the enormous size of the ship, its actual habitable area is comparatively small. This superstructure here, called the 'house', contains all the cabins, offices, recreation and meal space. On our ship the engine room starts directly below the house and stretches aft a ways toward the stern, and there are a few other storage rooms, for things such as paint, in other areas of the ship, but mainly the house is it. |

|

|

Topside, there are 9 levels: the 'Upper Deck', which is like ground floor, A (spoken as 'Alpha'), B, C, D, E, F, and G decks, and the Bridge. There is also a walkable space above the bridge, where the view is great but there is no protection from the weather. Here's a brief tour: |

|

|

Upper Deck:

Gangway, Tool storage, Entrance to Engine room, Laundry Room |  |

| A Deck: Security Office, Stores |

|

| B Deck: Officers' & Crew's mess hall, galley, Crew's rec room |

|

|

C Deck: Exercise room, pool, sauna |

|

|

D Deck: living quarters |

|

| E Deck: My cabin, Officers' rec room |

|

|

F Deck: living quarters |

|

| G Deck: living quarters, command office |

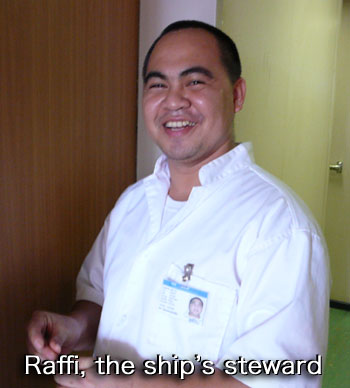

There were 22 men on the ship: 1 captain, 4 officers, 3 engineers, and 14 crew. Most of the officers were German, and all but one of the crew were Filipino, and they self-segregated themselves completely along European/Asian lines, with the Filipino 3rd officer choosing to dine with the crew and use the crew's rec room, while the German mechanic (crew) joined the officers and engineers in the officers' mess.

There were 22 men on the ship: 1 captain, 4 officers, 3 engineers, and 14 crew. Most of the officers were German, and all but one of the crew were Filipino, and they self-segregated themselves completely along European/Asian lines, with the Filipino 3rd officer choosing to dine with the crew and use the crew's rec room, while the German mechanic (crew) joined the officers and engineers in the officers' mess.  I never saw anyone using the officers' rec room, but the crew's was always a hive of activity. I attended a birthday party there for the Polish 2nd engineer, where the Filipinos were passing around a bottle of Fundador, a harsh brandy they loved.

I never saw anyone using the officers' rec room, but the crew's was always a hive of activity. I attended a birthday party there for the Polish 2nd engineer, where the Filipinos were passing around a bottle of Fundador, a harsh brandy they loved.

The 2nd officer gave me a tour of it my 2nd day, even letting me steer the ship (very briefly). "It is the most important piece of equipment on the bridge", he said, indicating the coffee maker. The lights are always kept off up there- they have to have their eyes adjusted to whatever the outside light level is, so if you go up at night, it'll be completely dark, except for in the map or radio rooms, which have blackout curtains around them.

The 2nd officer gave me a tour of it my 2nd day, even letting me steer the ship (very briefly). "It is the most important piece of equipment on the bridge", he said, indicating the coffee maker. The lights are always kept off up there- they have to have their eyes adjusted to whatever the outside light level is, so if you go up at night, it'll be completely dark, except for in the map or radio rooms, which have blackout curtains around them.

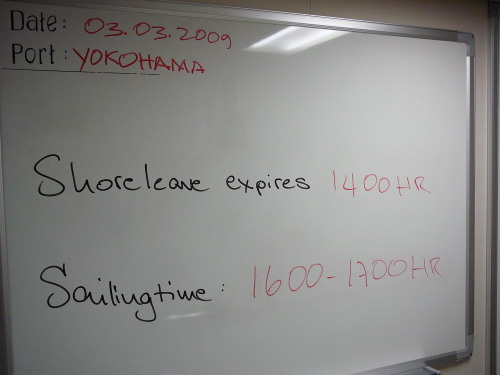

Containerized shipping allows for much faster loading and unloading than used to be possible, and one consequence of that is a greatly reduced shoreleave period for the ship's crew. In some cases, particularly when the port is a distance from the city proper, it's not even worthwhile to go ashore. When they do go ashore, it's typically only for a few hours, or in some cases overnight.

Containerized shipping allows for much faster loading and unloading than used to be possible, and one consequence of that is a greatly reduced shoreleave period for the ship's crew. In some cases, particularly when the port is a distance from the city proper, it's not even worthwhile to go ashore. When they do go ashore, it's typically only for a few hours, or in some cases overnight.

It seemed there was a range of skill among the 'stevedores', as the cargo loaders are called- in Yokohama, the gantry operator would pick up a box in a few seconds, whisk it to the target spot, and drop it into place like an expert Tetris player. In the American ports, especially Seattle, the operator seemed much less skilled, and would bang the container hard into adjacent ones when setting it down, as though using this hard physical contact deliberately to guide his work.

It seemed there was a range of skill among the 'stevedores', as the cargo loaders are called- in Yokohama, the gantry operator would pick up a box in a few seconds, whisk it to the target spot, and drop it into place like an expert Tetris player. In the American ports, especially Seattle, the operator seemed much less skilled, and would bang the container hard into adjacent ones when setting it down, as though using this hard physical contact deliberately to guide his work.

In the ports, they remove the heavy hatches that cover the hold, so they can access the containers below the top deck.

In the ports, they remove the heavy hatches that cover the hold, so they can access the containers below the top deck.| I had a good pair of binoculars with me that I had bought in Japan, and I spent a lot of time on the ship looking through them. The radar had a range much farther than human sight, and when a triangle-shaped blip appeared I would train my eyes in its direction as soon as there was any hope of seeing it. At first all you could see was an indistinct shadow, or a single point of light at night. As they got closer you could start to see the silhouette, and I came to recognize the basic types of ship from their shape. |

|

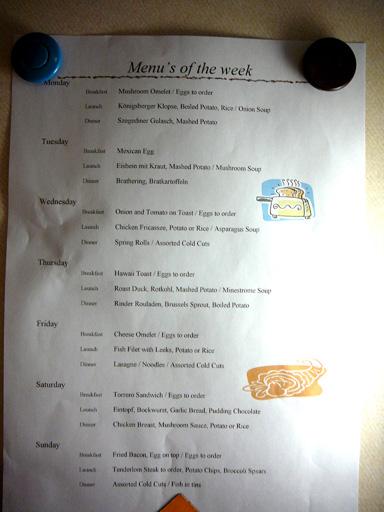

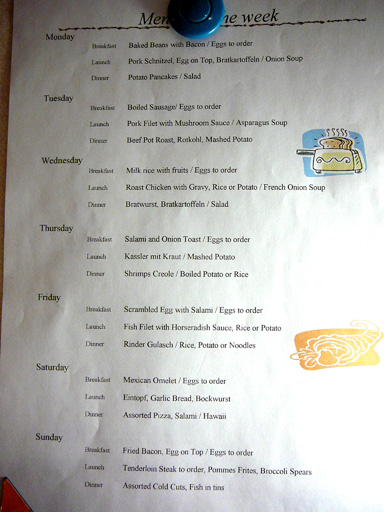

Meals

- Passengers take their meals with the ship's command in the officers' mess. Please note the following meal times (subject to change):

Breakfast 07.30-08.30

Lunch 11.30-12.30

Dinner 17.30-18.30

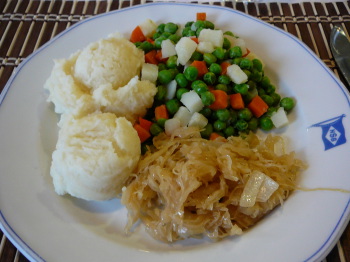

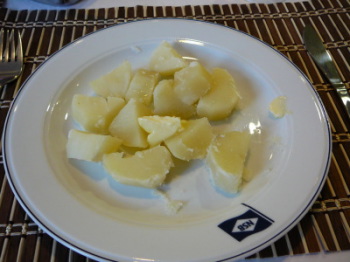

European and Asian home cooking is provided by the Philippine cook. In other words, passengers can expect hearty seamen's fare, which the cook prepares for passengers and the entire crew without making any distinctions. Apart from bread, jam, cheese and sausage, a warm dish is nearly always served in the morning and evenings. The drinks usually provided with meals (tea, coffee) are included in the travel price. Other drinks cost extra.

It is not possible to prepare special dishes for diabetics or vegetarians.

The cook has to make do with the provisions available up to the next replenishment. You should therefore not insist on the cook meeting any additional requirements.